The Pattern beyond the pixels – Reactive vs Proactive work

In the last post we introduced the project and the problem. We talked about how I dug into data and started asking specific questions to figure out why I was sensing a problem when both testers and management seemed happy with the progress. In this post we’ll dig into the first of several learnings: the difference between reactive and proactive work and switching from what is needed right now vs what would benefit us in the long run. I’ll also touch upon stress and how that affects us, since I think it is relevant to the topic.

When we left off I was trying to figure out why I was seeing all of these problems and antipatterns and no one else seemed bothered by it. The first thing I realised was this:

They didn’t have time to be worried – they were busy ”fixing”

What I realied when observing the teams for a while was that everyone was too busy with daily responsibilities to ever feel like they had time to look at improvements. They didn’t even feel like they had time to maintain the existing automation, add/update tests in sync with team deliveries and upskill in line with expectations on personal development. Thinking of whether or not they were doing the right things (in an efficient way) was just not on their radar. This can have a lot of reasons of course and figuring out the why behind this is as important as realising it is going on in the first place. (We will cover a few in this series actually)

The day of a tester in this context looked something like this. They would show up in the morning, read the nightly report to see if any of their tests were failing. Then they would analyse and debug those tests to find any actual potential bugs (in the test OR in the application code). If there was an actual problem with the test – that would hopefully be fixed right away but if it was an actual bug – this would be added as a task to be fixed and the test would be flagged until that fix would be in place. By now, interrupted by some meetings or other mandatory daily tasks, most of the day could be over. If there was time left, they tried to keep up with adding tests for new features or parts of the applications where the coverage was not up to par.

”It works when I run it locally”

If you can’t really figure out easily if a problem is an actual problem, and everything looks ok when you try to run it either locally or in isolation on the test environment – it is easy to just shrug, decide it’s just a flaky test and move on. You simply don’t think it’s worth the time and effort to properly solve the root cause. Maybe you hope it was just a random crazy happenstance and decide to let tomorrow’s you deal with it if not. Today you have more urgent things to do.

The problem is: It often is not magically solved tomorrow. And you likely won’t have more time tomorrow. In most places I’ve been – there is never enough time for technical improvements and refactoring. Even when the agreement is that we ”are allowed the time” – the time never seems to be enough. Unless you specifically make room for it, continuously and intentionally – reactive work always seems to take precedence.

Reactive work fills whatever void you give it. I doubt we will ever run out of work in our line of work! So we start complaining that we don’t have time. Someone should fix that so that we have time to do our job! How could we solve that? Well, we simply need more people! We need to keep up. So we add more people. Those people make the workload feel easier for a while so we finally start catching up on those new tests we need. Which adds to the workload. Which means it slowly builds again. Rinse and repeat.

A lot of people in our industry, developers and testers, are not very good at selling the story of why we need to invest in proactive work. Development is getting there. We know we need to work iteratively and improve as we go. We know we need to set aside a significant amount of time for things like slack (to have space for the unexpected) and refactoring (to avoid building debt). We know that not doing so will mean our ability to deliver will slowly degrade until it becomes so painful adding people will not even make a dent in it. Even when we know that – I think most of us still have to fight for it except for a few places where engineering practices are so much at the core it is built into the culture. For tasks that are not writing production code – I don’t even see that level of understanding. Debt is not just application code – it is everywhere. We need to prioritize improvement and reflection.

What I was seeing was a group of people meaning well but so caught up in what felt important now to have headspace or time to take a step back. But never looking at the bigger picture means building debt, which in turn means increased maintenance cost and less and less value delivered. And as a result, completing the cycle took longer and longer, which reduced the available time for improvement. The thing is, while you are in this loop – it is really hard to see it. And increasingly difficult to see any way to break the cycle. You start blaming everyone else. Someone else should do something!

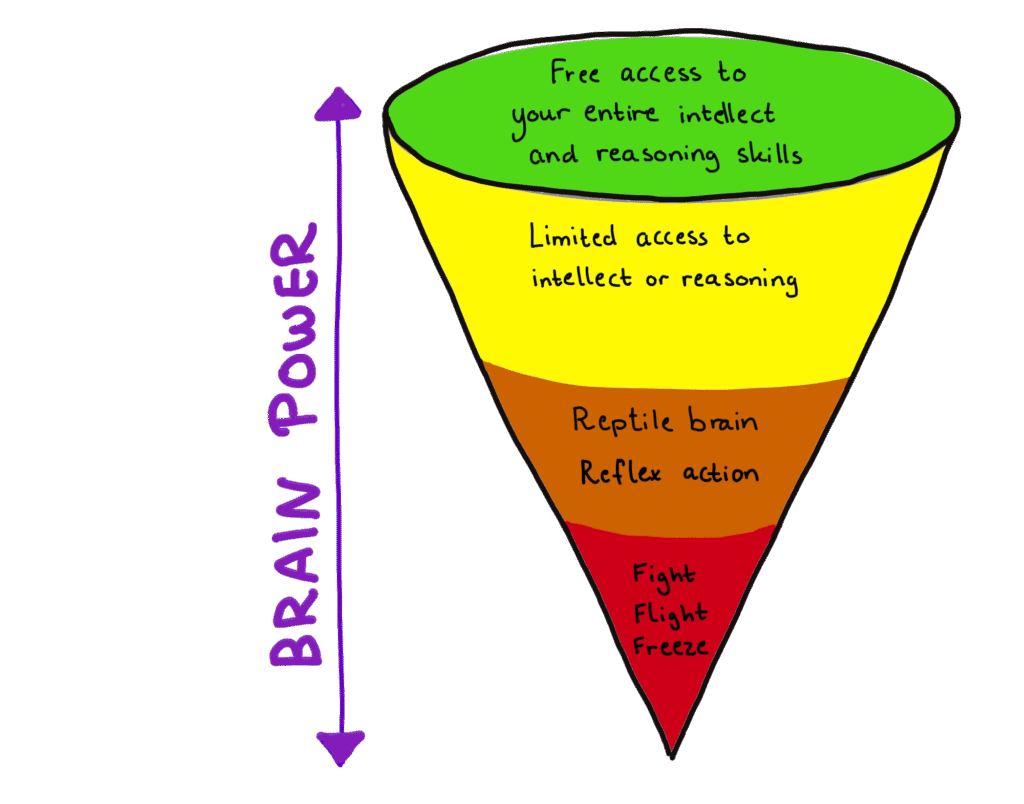

The Stress Cone

Stress has loads of bad effects on us. One of them being that it actually makes us less… smart. Or at least, less able to access our full intellect. Stress has a purpose, and that purpose was not to deliver story points on time. It was to make sure we maximised our chances of survival. Unfortunately, we cannot really differentiate between stress due to being chased by a giant bear or stress due to an upcoming performance review.

It also is very sneaky because unlike the acute stress of actually having to run for our literal life, work life stress can creep up on you. And your brain and body is trying to save you by moving one step at a time down the line to get you away from it. If there is a matter of life and death – you don’t want your brain to spend time and energy on analysing all options and weigh them against each other to come up with an optimal choice – you want to push your body to get you to safety NOW.

But in reality, when we are actually not in danger of death by deadline, this is not helpful.

So we end up in a really bad spiral. We stress, we get slightly less smart. We stress more, we get a bit more narrowminded. We stress even more, because why are we suddenly not capable? And we get worse. And so on. Until we either crash or break the cycle.

There are many ways of breaking the cycle (here are some self care exercises to try) but first you need to realise you are in it. Either by yourself or by someone else observing it and taking action. As a manager, I cannot create time. But I can, and should, be observant and act. One – because it is the humane thing to do. Two – because it is good for business. Unfortunately, managers are also humans – and thus just as prone to ending up in this bad cycle. We are also overall really bad at training and supporting managers.

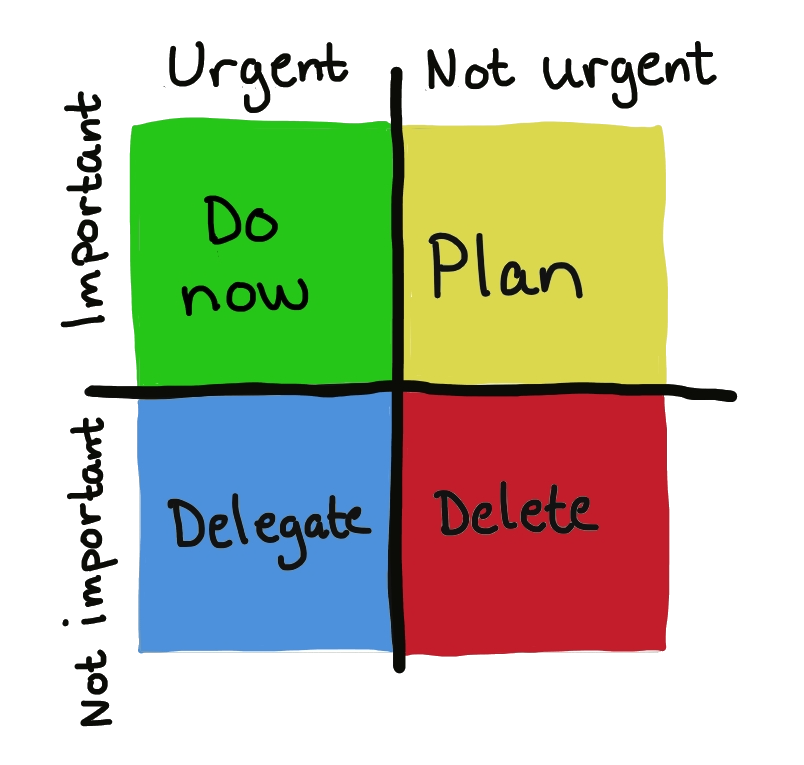

If everything is important – nothing is

One of the things people talk about all the time is how important it is to prioritise your tasks. There are tons of methods and articles talking about how to do it – it is also one thing I hear almost every manager complain about. Because there is always someone who thinks every task is the most important one and we have so many stakeholders, almost regardless of our role, and they are all pushing for their own agenda because that is what they are measured on.

One model I like is the Eisenhower matrix, dividing work into important or non important, urgent or not urgent. Termed by Stephen Covey and inspired by a quote by Dwight D. Eisenhower: “I have two kinds of problems: the urgent, and the unimportant. The urgent are not important, and the important are never urgent.” This is a nice goal to strive for, even if I’ve never felt even close to getting there.

Sit down and list all of the tasks you make in a week. At the end of the week, try to categorise them. I like doing two versions: one listing of where they fit in my current state and one listing where they actually belong.

So what do I mean by that? Well, there are different urgents. It might have been super urgent to order an extension to access rights for consultant A, because otherwise she could not work and a project would be delayed, but it should not have been – because it could have been planned and a project should not rely on one person being able to work a certain day. Urgent tasks have a true deadline and are dependent on time.

Important tasks should have an impact on long-term goals for you. Non-important tasks might feel important because someone is pushing you hard to do something so it is important to look closely and critically think about it. Is this a task that is important for real? And is it important that it is done by you, or could anyone do it? Might it even benefit someone else to do it, because it affects their goals more?

We want to spend as much time as possible on important but not urgent work. This is the sweet spot. And we want as little as possible in the important and urgent quadrant. If a task is neither important or urgent, why are we even doing it? And urgent tasks that are not important (that you do) can be delegated.

In my story so far, I was looking for the yellow quadrant work. The important stuff that would actually have a big impact. But people were stuck doing urgent – both important and not important – work. And since that work never decreased, because we didn’t spend time on the important but not urgent stuff, everyone got a bit of tunnel vision and didn’t see how to make space for impactful work.

As professionals, it is our job to make room for continuous improvements. Not getting heard? Find another way of delivering the message. What is the angle that will make someone listen? None of us can create time. I didn’t have better time creation skills as a manager, but a lot of people were annoyed and thought it was my job to do it. I can only very clearly state my view of it being important to work on proactive work. I can help you explain to anyone trying to squeeze more work in. I can sponsor you. But I can neither see that you need it unless you tell me, nor force you to actually prioritize it.

In part three we will dig into my next learning and talk about seeing the opportunity and enabling change.